What I am going to discuss today is my experience with and attempts to construct a 12 week undergraduate syllabus for the study of Genre Fantasy Literature.

So a couple of very quick disclaimers:

- This is not prescriptive; this is a starting point for discussion.

- This is based on my experience of teaching in the UK therefore it is a 12 week block comprised of four hours contact time each week, with a ‘reading week’ or ‘independent study week’ occurring in the second half of the semester.

- The four hours are divided between a 1 hour lecture, a 1 hour workshop in which the lecture is discussed and questions answered, and a 2 hour seminar discussion group in which the reading for the week is discussed in relation to the lecture and topic.

- In the UK system we favour essays over class tests so the examination criteria reflect this.

- The focus is on Genre Fantasy literature, not fantastic literature in general, SF, horror, genres of fantasy, speculative fiction. Therefore this is a pretty specific remit that does not take into account mythology, folklore, faerie tale, the Gothic, Weird Fiction, Science Fiction, Space Opera, the Fantastic, Fantastik, Fantastique, and so on. So there are a great many texts that have been excluded or that don’t fall under the rubric for the class.

- As with so many subject syllabi, this was an exercise in practical and pragmatic selection, so a number of texts were chosen for their expediency rather than their status or critical appreciation.

- The class is aimed at English Literature Students, it would be an elective module, and would be second or third year undergraduates.

- The module follows a thematic overview of Genre Fantasy rather than an historical perspective of the genre, although elements of genre history will obviously be discussed.

- Each of the three mini-sections utilises a single key primary text, in addition to excerpts from additional texts, short stories and critical works.

- Lastly, the focus of this class was to teach critical awareness of Genre Fantasy, Genre Theory, Literary Theory and to develop skills in textual analysis, and as a result texts were chosen that aided the teaching of the subject and that fitted in with the approach that I wanted to take.

So this is not a typical paper presentation. I thought I would take you through how I designed a Genre Fantasy Syllabus, and at the end we could discuss the pros and cons of approaching teaching this way.

Overview

Introduction

The first week of classes is given over to the endless discussion of defining fantasy. While there are no definitive definitions that conclusively encapsulate fantasy, by taking a chronological survey of the early fantasy texts and then workshopping some of the critical definitions the students should have a general appreciation of the tradition of fantasy narrative.

In particular, Armitt’s introduction, Clute’s definition in the Encyclopedia of Fantasy, and James & Mendlesohn’s definitions in A Short History of Fantasy give a broad appreciation of the various approaches to what Fantasy is.

However, by including Altman’s genre theory we can broaden the definition beyond fantasy specifically and take account of methodological bias that may be part of the fantasy definitions.

This first week then serves as a primer for the basic information necessary to challenge some basic assumptions students may have about the course, about fantasy and to set the tone for a critical awareness rather than a popular reading course.

Weeks 2-4

The next section is a three week block focusing on tropes, structures, clichés and potential narratological aspects that can help define the genre. The key text running through this section is Magician by Raymond E. Feist. As a D&D influenced text, Magician not only provides an example of the RPG style of fantasy text, but it also contains three key fantasy storylines, the mage, the warrior king and the politician.

The three weeks are then divided into World building and Magic Systems, which deals with diegetic formations and the importance of believable, limited settings. The Quest and the Balanced Party, which takes into account function, role and character as well as exploring the setting in terms of discontiguous narrative ludic spaces.

Lastly, the section deals with politics and social constructs in fantasy and the problematic nature of pseudo-medieval settings with modern socio-cultural power dynamics.

Weeks 5-7

The second core section is the practical application of literary theory to an example fantasy text. This is intended to hone students’ critical and analytical skills, reinforce their awareness of critical theory, and to bring that focus to bear on a fantasy text to demonstrate the usefulness of non-mimetic literature in providing fertile discussion of complex and often heated issues.

I chose Robin Hobb’s Ship of Magic, book one of the Liveship trilogy, to be the key primary text for this section for a number of reasons. The first being that I wanted to dispel the myth that fantasy is male only. The second is that the novel again contains three interweaving story threads allowing for interesting and dynamic interpretations. I have paired Hobb with excerpts from several other key fantasy texts. The Battle of the Hornberg from Tolkien’s LotR. Some small excerpts from Goodkind’s Sword of Truth. And some sections from Janny Wurts and Raymond E. Feist’s Daughter of the Empire.

Beginning with structuralism allows the students to examine what is happening, not necessarily what they are being told, and is a valuable exercise for undergraduates. Fantasy texts are often narrated from a subjective limited focalisation and present a simplistic moral polarity/binary. By taking the texts apart with a structural analysis they can re-examine what they are being told in a new light. Hopefully this will encourage critical analysis and greater free thinking.

Moving then to colonialism and post-colonialism brings in otherness, and entrenched cultural biases and solid examples of power hierarchies on a grand scale.

This then becomes refined to the personal political in the last section by investigating feminism and fantasy.

Week 8

Week 8 is traditionally when a ‘reading week’ happens. This gives the students a chance to consolidate notes, work on their paper, and have time to meet with lecturers to address any issues or problems they are having with the work.

Thus far the sections have focused on basic foundational work and then the application of general literary theory. The last section moves on to discuss fantasy specific analysis, and an understanding of the nuances within the genre, as well as some broader concepts.

Weeks 9-11

The key text here is Erikson’s Gardens of the Moon which manages to be a subversive, post-structural and post-modern fantasy narrative, while at the same time remaining firmly in the the centre of the genre.

The first week of this section focuses on finding formulas, and understanding the differences between formula, patterns, structures, tropes and clichés in relation to defining the genre specifically. So it is a return to the earlier part of the module, but the students should be much more prepared to enter into discussion and to deconstruct assumptions about ‘generic’ fantasy.

The next week shifts the focus from formula to parody. Thereby highlighting different aspects of subversion, and inversion and bringing in concepts of meta-narrative and meta-text.

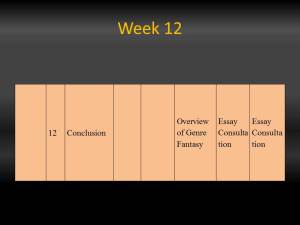

Week 12

The last teaching week brings together the concepts of subversion in relation to Erikson’s Gardens of the Moon and basically is a primer for the set extended essay coursework.

Overview

Primary Texts

Eddings, David and Leigh Eddings, The Rivan Codex, (London: Voyager, 1999)

________, Pawn of Prophecy, (Belgariad, 1) (New York: Ballantine, 1983; repr. London: Corgi, 1993)

Erikson, Steven, Gardens of the Moon, (Malazan Book of the Fallen, 1) (London: Bantam, 1999)

Feist, Raymond E. and Janny Wurts, Daughter of the Empire, (Empire Trilogy, 1) (London: Grafton, 1988)

Gemmell, David, Legend, (Drenai Saga, 1) (London: Orbit, 1984 repr. (London: Arrow, 1986)

Goodkind, Terry, Wizard’s First Rule, (Sword of Truth, 1) (London: Millennium, 1995)

Hobb, Robin, Ship of Magic, (Liveship Traders, 1) 2nd edn, (London: Voyager, 1999)

Pratchett, Terry, Witches Abroad, (London: Gollancz, 1991)

Tolkien; J. R. R., The Lord of the Rings, 2nd edn (London: Allen & Unwin, 1966)

Weis, Margaret, ‘The Best’ in Dragons of Krynn (Cambridge: TSR Inc., 1994)

Critical Texts

Books

Abbot, H. Porter, The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative 2nd. edn. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

Altman, Rick, Film/Genre, (London: British Film Institute, 1999)

Armitt, Lucie, Fantasy Fiction: An Introduction, (London: Continuum, 2005)

Attebery, Brian, The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature: From Irving to Le Guin, (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1980)

________, Strategies of Fantasy, (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1992)

Barry, Peter, Beginning Theory (Manchester: MUP, 2009)

Beebee, Thomas, The Ideology of Genre: A Comparative Study of Generic Instability, (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994)

Brooke-Rose, Christine, A Rhetoric of the Unreal: Studies in Narrative and Structure, Especially of the Fantastic, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981)

Campbell, Joseph, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, (London: Abacus, 1975)

Card, Orson Scott, How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy (Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1990)

Chatman, Seymour, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and

Film (New York: Cornell University Press, 1978)

Clute, John and John Grant; eds, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, (London: Orbit, 1997)

Clute, John, and Peter Nicholls, eds, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, (London: Orbit, 1999)

Currie, Mark, Postmodern Narrative Theory (London: Macmillan, 1998)

Fishelov, David, Metaphors of Genre: The Role of Analogies in Genre Theory, (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993)

Hume, Kathryn, Fantasy and Mimesis: Responses to Reality in Western Literature, (New York: Methuen, 1984)

Jackson, Rosemary, Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion, (London: Methuen, 1981)

James, Edward and Farah Mendlesohn, eds, The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Mendlesohn, Farah, Rhetorics of Fantasy, (Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2008)

Moorcock, Michael, Wizardry and Wild Romance, (London: Gollancz, 1987)

Propp, Vladimir, Morphology of the Folktale, ed. by Svatava Pirkova-Jacobson and trans. by Laurence Scott, (Philadeplphia: American Folklore Association, 1958)

Senior, W. A., Stephen R. Donaldson’s Chronicles of Thomas Covenant: Variations on the Fantasy Tradition, (Kent State University Press, 1995)

Todorov, Tzvetan, The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, trans by Richard Howard, (New York: Cornell Paperbacks, 1975)

Waugh, Patricia (ed) Literary Theory and Criticism – An Oxford Guide ( Oxford: OUP, 2006)

Wynne Jones, Diana, The Tough Guide to Fantasy Land, (London: Gollancz, 2004)

Articles

Clute, John, ‘Grail, Groundhog, and Godgame’, JFA, 10:4 (2000), pp.330-337.

Devitt, Amy, ‘Integrating Rhetorical and Literary Theories of Genre’, College English, 62:6, (2000), pp.696-718

Kelso, Sylvia, ‘The King and the Enchanter: gender, power and authority in Patricia McKillip’s fantasy novel’, The New York Review of Science Fiction, 18:6 (2006), pp.8-12

Kincaid, Paul, ‘On the Origins of Genre’, Extrapolation, 44:4 (2003), pp.13-21

Mendlesohn, Farah, ‘Towards a Taxonomy of Fantasy’, JFA, 13:2 (2002), pp.169-83

________, ‘Conjunctions 39 and Liminal Fantasy’, JFA,15:3 (2005), pp.228-39.

________, ‘Crowning the King: Harry Potter and the Construction of Authority’, JFA, 12:3 (2001), pp.287-308

Vander Ploeg, Scott and Kenneth Philips, ‘Playing With Power: The Science of Magic in Interactive Fantasy’, JFA, 9:2 (1998), pp.142-56

Very comprehensive!

LikeLike

It was an experiment to do something that wasn’t chronologically organised and would be easy to swap in and out various texts to make the course easily update-able, renewable, and would still be useful to students.

LikeLike

Hey, A-PC: Thanks for posting this–very helpful. Looks like I’ll be adopting and adapting this for the fall, in a hybrid course that focuses on more broadly construed fantasy, and adds some film components in addition…over a 15 week semester. Thanks for including my co-written article in the critical works listing! Scott v/d P

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad it was of help. Let me know how your course goes (and if possible send me a copy of the syllabus) because I am always interested in seeing how other people construct and teach the genre.

LikeLike

ReadWriteThink couldn’t publish all of this great content without literacy experts to write and review for us. If you’ve got lessons plans, videos, activities, or other ideas you’d like to contribute, we’d love to hear from you.

LikeLike

I very much appreciate the critical materials, especially the articles. I have a good sense of what primary lit I want to do, but I’ve been struggling to find the right voice for criticism that won’t overwhelm students’ own questions. Thanks!

LikeLike