With the exception of Dragons, one of the most recognisable ‘monsters’ of genre fantasy is the humble Orc. Orcs, commonly found in hordes™, are the disposable foot soldiers of every evil wizard’s army, and are useful opponents/victims for would-be heroes-in-training. They are evil, barbaric, ugly, brutal and, above all, monstrous. But given the trend of modern Genre Fantasy to move away from simplistic moral polarities to more complicated moral relativistic positions, can we still treat and react to Orcs in the same way? With some notable exceptions, Mary Gentle’s Grunts (1992) and Stan Nicholls’ Orcs (1999-present), the treatment of Orcs has remained fairly consistent ever since Tolkien popularised them as the enemies of the hero.

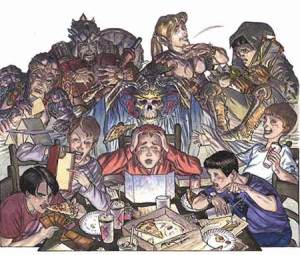

Using established critical techniques already associated with the fantastic, in particular the Monstrous Other, Otherness, and the psychological readings of Monstrosity, the position of the Orc will be established in the context of the genre. Then, by examining how the Orc has been used in related fantasy media, such as the RPG, it will be shown how the function of the Orc has changed into a ‘disposable’ monster. Lastly, with the Orc as a cypher for almost every evil sentient monster deployed in Genre Fantasy, this paper will examine how we ‘read’ Orcs and suggest that the true monstrosity is the reader’s casual acceptance of racial genocide rather than the Orc’s position as Monstrous Other.

I took the idea of monstrosity as being constructed through a limited, subjective and external perspective and this therefore limits empathy with the subject. By considering the narrative from the perspective of the monster we gain a new view of the story and of monstrosity.

With the exception of Dragons, one of the most recognisable ‘monsters’ of Genre Fantasy is the humble Orc. Orcs, commonly found in hordes (Which I believe is the ™ term), are the readily identifiable disposable foot soldiers of every evil wizard’s or Dark Lord’s army, and they are the ever useful opponents for would-be heroes-in-training. But given the trend of modern Genre Fantasy to move away from simplistic moral polarities to more complicated moral relativistic positions, can we still treat and react to Orcs in the same way? Is it time to re-evaluate Orcs and as a result, the texts in which they appear? Can we now view Orcs as the victims of the self-proclaimed heroes? With some notable exceptions, Mary Gentle’s Grunts (1992) and Stan Nicholls’ Orcs (1999-present), the treatment of Orcs has remained fairly consistent ever since Tolkien popularised them as the enemies of the hero.

I am sure that everyone here is familiar with the Orcs of Tolkien’s world. We could describe them as barbaric, evil, corrupt, treacherous, cannibalistic, and irredeemably evil.

In short they are ugly, snarling monstrous creatures.

Yet they are clearly also sentient, some are at the very least bi-lingual. As Tolkien points out:

To Pippin’s surprise he found that much of the talk was intelligible; many of the Orcs were using ordinary language. Apparently the members of two or three quite different tribes were present, and they could not understand one another’s orc-speech.’ P.580 (The Uruk Hai – The Two Towers)

So clearly these Orcs speak at least two maybe even three languages: The black Speech of Mordor, their own Orcish language, and Common.

Therefore not all Orcs are the same. There are different tribes with different languages, and given that language and culture are intertwined, we could at least argue that there may be significant cultural differences as well. Certainly the most obvious example is made apparent between the Mordor Orcs and Saruman’s Uruk Hai, as the dispute between Grishnakh and Ugluk in The Two Towers clearly demonstrates.

But that conflict also proves that Orcs can evaluate social or group goals and needs in addition to their own personal goals and ambitions. They have loyalties, can choose to follow orders and possess at least some element of free will. They understand social and cultural hierarchy as well as individual positions of power. Grishnak and Ugluk argue over what to do with the Hobbits, should they killed, should they be brought to Sauron, should they be searched. There is tension between the Orcs as they struggle to assert personal dominance as well as the dominance of their respective allegiances and military hierarchies.

What is clear is that they can reason and explain their reasoning. In effect, these are sentient beings, they are rational, thinking people… at least to some extent.

And while they appear cruel, at least by our standards, they feed Merry and Pippin their Orc-draughts to give them enough energy to keep running. In effect they demonstrate some level of compassion for their prisoners, minimal though it may be, and for which the motivations are not necessarily discernible or clear, as Tolkien does not investigate the Orcish perspective given his focus on the Human and Hobbit perspectives. But these Orcs are not creatures, they are not monsters, and they are not dumb animals.

So where can we find stories that address this lack of Orcish voice, that give us the perspective of the Orcs, that tell the story from the Orc side of the war.

A book that purports to redress this balance is, of course, Mary Gentle’s Grunts!.

Gentle takes the Orcish perspective as a group of Orcs prepare for the great battle between the forces of good and evil. However, this is not a ‘straight’ redressing of the imbalance of perspective, it is, from beginning to end a pointed satire or parody of a perceived stereotype of genre fantasy fiction, the great war.

Yet despite being a parody of the good versus evil cataclysmic battle/apocalypse, trope that appears in much early Genre Fantasy, Gentle does attempt to give voice to the Orcs, who despite being nearly ubiquitous in their appearance in diverse fantasy series, are a peculiarly voiceless and underrepresented fantasy race, narratorially speaking.

But this synopsis is slightly disingenuous. While Gentle begins with a focus on the Orcish perspective she rapidly ‘alters’ the Orcs. That is to say, by introducing an external magical factor, a geas or magical spell on the weapons the Orcs find in the dragon cache. She alters the Orcs, changing the Orcs from recognisable fantasy characters to caricatures of US Marines fighting a war in a fantasy world.

Barashkukor straightened his slouching spine until he thought it would crack. The strange words the big Agaku used were becoming instantly familiar, almost part of his own tongue. No magic-sniffer, he nonetheless felt by orc-instinct that presence of sorcery, geas or curse. But if the marine first class (Magic-Disposal) wasn’t complaining… He fixed his gaze directly ahead and sang out: ‘We are Marines!’. P.51

The introduction of an external force to ‘change’ the Orcs allows them to behave in different ways, to act contrary to their established fantasy characters and characteristics. This is of course perfectly in line with Gentle’s focus and intention for the novel, to lampoon the ossified ‘Ultimate Battle’ motif that seems to recur with alarming regularity.

However, this means that the inversion of the Tolkien type Orc is used only for comic effect and does not actually attempt to give a voice to the Orcish world view, or attempt to actually investigate Orcs in anything other than parody. In effect, Gentle’s work ultimately fails to provide the Orcs with their own voice, to represent their world view and it fails utterly to present the Orcs as an actual race of rounded developed characters. Only their Marine characters and characteristics are given full voice.

Another narrative that purports to tell the Orc side of the story, is Stan Nicholls’ Orcs. This is a series of fantasy novels which tells the story of a fantasy world’s battles from the Orc perspective, following the trials, tribulations and adventures of Orc Captain Stryke and his warband The Wolverines. This series is not a parody, it is not a satire and it is not attempting to lampoon fantasy cliché. For all attempts and purposes Nicholls appears to be writing the very thing I am talking about, a fantasy series from the perspective of the much maligned Orcs.

However, rather than using the narrative opportunity presented by Tolkien in The Two Towers, that is the rare insight we get to Orc internal politics and the tensions between Mordor Orcs, Mountain Orcs and Sarumans fighting Uruk Hai, Nicholls uses an old ‘bait and switch’. In the first chapter the Wolverines are sacking a human village and come across a baby.

The cries of the baby rose to a more incessant pitch. Stryke turned to look at it. His green, viperish tongue flicked over mottled lips. ‘Are the rest of you as hungry as I am?’ he wondered.

His jest broke the tension. They laughed.

‘It’d be exactly what they what they’d expect of us,’ Coilla said, reaching down and hoisting the infant by the scruff of its neck. […] ‘Ride down to the plain and leave this where the humans will find it. And try to be … gentle with the thing.’ pp.13-15

Unfortunately the ‘gentle’ there is a coincidence.

Nicholls has done much the same as Gentle in that he has changed the Orcs to something much more sympathetic. He has rewritten what an Orc is and in effect reduced them to another fantasy cliché, that of the noble savage, the barbarian tribesmen, the put upon native people who have an overriding sense of honour that has been abused by ‘evil’ masters. These Orcs are the unwilling servants of a Dark Power.

So again this is another attempt to redress the narrative imbalance of a widely used fantasy race that suffers from a seeming lack of ability to genuinely conceive of what Orcs are like, despite the fact that this is clearly evident from Tolkien’s work.

Yet there are examples in which Orcs remain Orcs and yet their stories are accessible, their point of view is articulated and they are given a voice.

While not exactly the most respected or critically examined areas of fantasy literature and narrative, D&D and the various worlds and fantasy series associated with it provide a fascinating perspective on the evolution of Orcs as a fantasy race.

What is interesting is that D&D had to confront an issue with Tolkien’s initial construction of the Orc. If Orcs are sentient then why were they treated as monsters and not simply as enemies? Early editions of D&D used Orcs in much the same manner as bad fantasy does, they were simply a stack of low level cannon fodder enemies to be killed off by the heroes to prove how wonderful Sir- Killalot and Princess Smack-them-in-the-head are.

However, as the game developed and grew increasingly more complex, in part to continue to expand the world so that players had greater variety and choice and therefore would keep buying more supplements and products, but also because as the fantasy world grew and the game developed it became increasingly more sophisticated and began to probe and investigate difficult areas of what is assumed to be a simplistic paradigm. If you can have half-elves, half-dwarves, as playable characters etc… can you have half-orcs?

If you can have half-orcs as playable characters, can you have full blooded orcs as a playable characters? How does Orc society actually function? What are Orcs actually like?

In order to continually develop D&D for market, the company continued to add races and playable character types, including some that the confining ‘moral alignment’ rules describe as evil. Orcs have gradually entered the game as a playable race, equal to and on par with Elves, Humans and Dwarves.

D&D is not the only game to do this. Orcs appear as playable races in a number of Gamesworkshop products (Warhammer, Warhammer 40K, Blood Bowl, etc.)

However, the simple inclusion of something called Orcs (as Nicholls has proven) does not necessarily guarantee that they remain identifiable as Orcs.

So let us consider R.A.Salvatore’s Legend of Drizzt Series, a long running (and still ongoing) fantasy series concerning the adventures of a Drow (Dark Elf) and his companions. In The Hunter’s Blades Trilogy {The Thousand Orcs 2002, The Lone Drow (2003) and The Two Swords (2004) (books 15-17 of the Legend of Drizzt series)} one of the major secondary narrative strings is a developing storyline about an Orc chieftain or warlord Obould Many Arrows. Obould Many Arrows, is initially allied to a clan of Frost Giants and has amassed a massive horde TM. In other words he has called together a large military force or army… but as he is an Orc we are stuck with horde.

As the books develop his army manages to push the Dwarves back to the gates of the Dwarvish realm, Mithral Hall. And the purpose of this conflict is to clear space in the foothills of the Dwarvish mountain range so that the Orcish clan can establish a genuine kingdom free from the interference of giants, dark lords, evil wizards etc. And so that Obould can open diplomatic relations equal to Elves, Dwarves and Humans. In effect, to create a recognised Orcish sovereign territory.

What makes this interesting is not that there is an Orc horde, but that the purpose of their ‘invasion’ is actually to find a kingdom and land of their own. They ‘push’ the Dwarves back to their own Kingdom… which without too much thought you realise means that the Dwarves can be redefined as evil imperialistic conquerors hell bent on wiping out another race in order to steal land and wealth. Not that Salvatore does this, but the subtext is present.

The Orcs on the other hand are pushing the Dwarves back. In essence containing an evil expanding army… The Orcs are not ‘stealing land from the Dwarves, the Dwarves live underground, they don’t need nor use the land above the mountain, the lower slopes of the mountain are free, unoccupied and not in use.

And the purpose of the Orc army is not to kill off the other races, it is not to destroy the forces of good, it is to create a consolidated home land where the Orcs can live free from persecution and being hunted down like animals.

In effect then, Salavatore has done something that Gentle and Nicholls could not, he has created a political, interesting and engaging storyline which considers and addresses the Orcish perspective without altering who and what Orcs are. In hindsight it seems strange that no-one thought to do this before. Yet the earlier examples given could not seem to conceive of the Orcs as anything other than monsters.

Returning then to the LotR with this new perspective of Orcs we need to reconsider them in this new light. While Tolkien at least focused on the fact that Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas weighed their decision and chose to try and rescue Merry and Pippin at the beginning of The Two Towers, Jackson’s film adaptation is more revealing of my point.

When Aragorn turns to his companions and says with barely restrained glee ‘We travel light. Let’s hunt some Orc’[1] we can now see how this reduces a sentient and potentially ‘redeemable’ species to an animilaistic and monstrous fate.

But Jackson is not entirely to blame because aspects of this concept, this attitude, appear in Tolkien’s work. At the battle of the Hornberg in Helm’s Deep Legolas and Gimli have a competition to see who can kill the greatest number of Orcs. This friendly competition is presented in an heroic light and in the film adaptation is even a source of humour.

But if we consider this episode from this new perspective, counting the number of Orcs killed now appears as crass, distasteful and even malicious behaviour. In effect it appears as a mis-guided glorification of the murder of enemies and rather than the joyous celebration of monsters put down.

Furthermore, in this battle the remaining Orc horde is herded into an indefensible position surrounded by the Ents and Huorns, who then, rather than letting them surrender, simply destroy them, off page, without a sound, without a murmur, without a second thought. Tolkien describes this in fairly unambiguous terminology:

‘Wailing they passed under the waiting shadow of the trees; and from that shadow none ever came again.’[2]

Yet, while this is a cause for the heroes to celebrate, the Orcs were an enemy that need to be defeated, why do we as readers never once consider that this is the systematic extermination of a race. That this is mass murder. That this is attempted genocide. The heroes might feel justified in their attitudes as such positions might be necessary in war and combat, but for readers, surely we should question the heroes’ actions.

The heroes do not take Orcish prisoners.

The heroes do not even set up forced labour camps or prisoner of war camps. All enemy combatants, even if they are retreating or have surrendered, are slaughtered.

When it comes to honouring the dead, the heroes do not give the Orcish dead a modicum of respect or attempt proper funeral rites, rather they are stacked and burned or tossed into mass graves.

So if we have never questioned this it seems that we as readers, not actually involved in the war, tacitly or openly agree with the mass extermination of an entire species, we revel in the slaughter of a sentient race, we delight in the murder of surrendering enemy combatants, we never once treat Orcs as people, as a sentient species, as a race that may be on the other side of the war, but still deserve consideration and respect.

In short, Orcs aren’t monsters. We are.

[1] The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (dir. Jackson, 2002)

[2] Tolkien The Two Towers Chapter 7 ‘Helm’s Deep’ p.707

(Originally delivered as a paper at ICFA 35 and a variant published in NYRSF)